10 September, 06

Bovec, Slovenia

Hola!

So I need to offer a bit of explanation. The last two posts I put up on

my page, maybe even the last three, took forever to finish. I’ve been

writing some in the days since then, but a lot of what I’ve been doing

has been other things, and finishing those posts off, getting them

ready to be put online, once I found a wifi connection. As of today, I

am caught up, and not working on other things at the moment, so I’ll go

back to writing in the present tense, as it were. I still have to write

about things that happened a few days ago, but that’s how its got to

be, as I refuse to lug the computer around with me and report on things

as they are happening. This ain’t CNN people.

So first, a little update. Thursday was spent touring the Chernobyl

site, and the area around, and that is what most of this is going to be

about. To be honest, it could be three or four posts, easily, and this

is going to be a long one. Tons of pictures too… I was doing good stuff

that day, though I have yet to go through and begin choosing pics to

put up, so it may take me a couple days to get this up.

Friday was spent traveling. I left my hotel in Kiev at 5am, took a 40

minute taxi ride to the airport, caught my flight with ease (the Kiev

airport was fantastic, actually) and cruised through the day. Three

hour layover in Prague, Another flight to Zagreb was spent talking to a

woman with gorgeous green eyes from Frankfurt, Germany named Nadja, but

landed us in pouring rain. She was picked up by relatives, I grabbed a

bus into town. I then tried to pick up a package my mother sent me with

various gear for the rafting trip, but after being shuffled around

between various windows and procedures for a while, it came to light

that in order to actually get the package, I would have to go to the

international post office, next door, which was already closed for the

weekend. (At 1pm, I arrived in Zagreb at 3pm, so there was no hope).

With that, I caught a train to Ljubljana, Slovenia, leaving my teva

sandals and other gear to hang out in Zagreb and be picked up in a week

or so when I get back there. Finally, around 9:30 that night, I got off

the train and pretty quickly found a nice place called the City Hotel

to crash.

Saturday I got up, bought a bus ticket to Bovec for that evening, then

spent the day wandering. Ljubljana is nice, and I’m looking forward to

going back there, but Bovec is really nice too. It’s a tiny town in NW

Slovenia, very close to the Italian border and the city of Trieste. It

reminds me powerfully of home, as it’s surrounded by mountains, and is

the headquarters for about 12 different companies that offer rafting,

kayaking, mountain biking, climbing, paragliding, skydiving, and every

other adventure sport you can name. Growing up in West Virginia, I

spent a fair amount of time rafting and hanging out in towns like this.

Everything is geared around the tourist and sports industries… There

are at least three or four outdoor shops, and about half of them keep

hours like 8am – noon, 4pm – 7pm. Because noon to four are spent on the

trails or on the water, don’t you know.

Anyway, more about Bovec later, after I’ve experienced it a bit more.

For now, I am dying to talk about Chernobyl.

In April of 1986 I would have been gearing up for the end of my Junior

year of High School. My Junior Prom was probably around the end of the

month, and I took Andrea Metz, my first true love, and the girl who

broke my heart for the first time the following summer. At that point,

we would have been in pretty much the high point of our relationship,

spending as many evenings as we could arrange hanging out in her

basement, listening to Split Enz, Talking Heads, Berlin, and every

other New Wave band of that era. The couch in her basement was where I

got a great deal of my sex education, but didn’t actually lose my

virginity, probably due to equal parts my own shyness and her intention

to remain a virgin, for at least a while. She did teach me to kiss, and

for that, if nothing else, I owe her a huge debt.

I’ve been thinking a lot, the past few days about what I would have

been doing around the end of April because, while I remember hearing

about the Chernobyl accident, I didn’t remember much about it. In

contrast, when the space shuttle Challenger exploded the following

year, I remember exactly where I was and how I found out. For any of

you reading this, I’d be curious to hear how much you remember. I knew

it was a big accident, certainly, but it really didn’t make a big

impression. Do any of you remember more? Think about it before you read

on…

Part of the reason it didn’t make a big impression might be the way

that information trickled out. First some European countries started

raising hell over radiation levels that were far above normal, then

slowly the details about what happened came to light. In short, what

happened is this: Reactor #4 was partially shut down to conduct an

experiment relating to steam pressure just previous to being completely

shut down for some routine maintenance. A confluence of factors

including poor reactor design, poor training for the operators, and

some quirks of the experiment and timing created a problem that may not

have even been noticed by the operators, and when they went to shut

down the experiment, the reactor quickly began to overheat and caused a

massive explosion of steam that blew the concrete containment lid, as

well as everything above it to pieces and started a graphite (the

control rods were made of graphite) fire right in the heart of the

reactor.

Over the next few hours, and then days, thousands of souls risked their

lives, and in some cases, gave their lives, to keep the catastrophe

from being even worse. Firefighters struggled to put out an intensely

hot fire without any radiation gear to protect them. Nearly all of them

died within a few weeks of radiation sickness. Once the fire was out,

the reactor was continuing to heat up, and was threatening to melt

through the floor of the chamber, at which point it would have hit the

water sloshing around from putting out the fire and caused an explosion

even bigger than the first one. Miners were brought in from all around,

thousands of them, and they dug tunnels under the reactor core, then

reinforced the floor with concrete slabs to keep that from happening.

Helicopter pilots flew above the smoldering core dropping bags of sand

and concrete and anything they could find to try to stop the meltdown.

Each time they dropped a load of sand, though, radioactive dust was

thrown into the air all around them. Most of those men – the miners and

the pilots – have probably died over the last twenty years. Finally,

once the meltdown had been averted, thousands of soldiers were brought

in to clean up the radioactive debris by shoveling it off the roof and

into the ruins of Reactor #4. Over 5000 men donned suits made of lead

and rubber and spent two minutes on the roof in teams of four (three

working, one watching the geiger counter and the stopwatch) shoveling

debris. At the end of that two minutes, they went back inside and their

two years of compulsory service was over. Approximately one third of

them (18 – 22 years old at the time) are now dead.

A man named Vasily was living in the nearby city of Privyat.

He had grown up in a village nearby and worked as the chauffer for the

head engineer of the Nuclear Power Station. Privyat was only four km

from the plant, and had been built as a Soviet Model city only 16 years

before. The population of 60,000 or so were well aware that something

had happened (the cloud above the station from the fire supposedly

glowed green for two nights) but were allowed to stay for almost two

full days. When they finally were told that they would be evacuating

the town, they were told it was only for three days. It was an

intentional lie designed to make the evacuation as fast as possible. If

people had known they were leaving forever, they would have tried to

take more of their belongings. Instead, they brought only enough for a

few days, leaving most of their valuables behind, and the city was

quickly and efficiently loaded onto buses and taken to Kiev, about two

hours to the south.

I could go on… obviously, but there’s too much to tell. The Soviet

system was still highly entrenched, and appearance of control was as

important as anything. For that reason, May Day celebrations, a few

days later, went on everywhere, including Kiev, where radiation levels

were far above normal even two hours away from the plant. A film I saw

of those celebrations was punctuated by white flashes every couple

seconds – gamma rays hitting the film and over exposing big chunks of

the frame.

Today, Chernobyl is officially closed to the public. There are

checkpoints at all the roads 30 km from the Plant. A circle 40 miles in

diameter (pretty much all of the Austin area, I think, from far south

to far north). There is another checkpoint at the 10 km distance. About

3000 people work inside the 30km circle, on various aspects of the

cleanup, and another 3000 work inside the 10km circle, mainly right

around the plant. A bit less than a thousand people have move back to

their homes within that area, living illegally but still with basic

support from Ukraine. Mainly they are the elderly and people whose

entire lives were tied to their homes and land. If you work inside the

exclusion zone for 7 years, you can retire early. Women can retire

early after 5 years. Everyone is monitored closely, and work each day

only as long as it takes to reach the designated level of exposure. For

those in the 30km zone, it will usually be full days. For the welders

working on the structure of Reactor #4, that might be only two minutes

or so. After that, they are taken by train or bus back to their homes

outside the zone.

About six or seven years ago, visitors were allowed to start coming

into the zone for a hefty fee. Now, there are a few different tour

operators, and depending on how many people are in your group, you’ll

pay anywhere from $150 to $500 for a few hours seeing the town of

Chernobyl (about 20km away from the plant), the town of Privyat, the

Power Plant, and whatever else the tour operator and representative

from the Ministry of Information (one accompanies every tour) allow or

want you to see.

I’d wanted to take this tour from the time I read it was possible, but

to be honest, I kind of forgot about it until about a week or two

before I was headed to Ukraine. Way too last minute (the week before) I

sent emails to a few different places, telling them the dates I was

going to be available, and asking if they had any openings or tours

scheduled. Luck was with me, and a man named Sergey emailed me back,

allowing me to join a tour already scheduled for Thursday, September 7

for $150. We’d meet at a central hotel at 9am, drive to Chernobyl, take

the tour, then have lunch, and be back in Kiev that evening. So, I

rearranged my travel plans and fixed it so that I could take the tour

on the 7th and still be down in Slovenia on the 9th for the kayaking

trip. It meant buying a $370 plane ticket to cover that distance in

time, but I figured the tour was on the cheap side, and there would be

plenty of times for me to see Prague and Budapest later. What the hell,

I’m on vacation, right? What’s $520?

So, Thursday morning I showed up at the designated place and time, and

quickly met Sergei, a stocky middle aged Kiev native, and my fellow

tourists – Three Scottish guys named Matt, Greg and Philip. Sergei put

us on a tank-like bus, said he’d meet us at the checkpoint, and just

like that, we were on our way.

(Phillip, Matt and Greg, along with the Blue Tank)

After driving about an hour or so, we stopped in a little town and

picked up Sergei again, who seemed to be leaving his car there for

convenience. Later I discovered that we were returning to Kiev late

into rush hour (Traffic in Kiev is madness. My first day there I saw

the stereotypical stalled intersection with cars in all four directions

stopped in the middle of the intersection as the lights changed again

and again and again. I’ll never bitch about American drivers again. At

least most of us seem to grasp that you have to leave the intersection

open rather than trying to be the last car through the red light, to

keep madness from happening.) and Sergei wanted no part of that (smart

man).

About an hour after that we hit the first checkpoint. It was pretty

simple, just a couple small buildings and a roadblock, but the soldiers

were armed and checked our passports pretty thoroughly. Once through

though, there wasn’t really anything to keep us from going where we

wanted. We drove until I started noticing buildings behind the line of

trees. This was the village of Chernobyl, and just looking up the road

in front of you, you’d never notice it. Only looking to the side, where

you could see into the trees (not far, as in most cities the buildings

only stood back from the road by twenty feet or so) did you notice that

there was an entire town there. We drove through the town and then

finally saw some more modern buildings, or at least ones that had been

maintained, and soon enough turned into a driveway and parked behind

one. We had arrived at the Ministry of Information, an obviously SSR

inspired name for authorizing tours and I assume any other bits of

knowledge that might escape the exclusion zone. I say that, but Sergei

(yes, both our guides were named Sergei), a dark, sedate man in jeans

and a denim shirt with a thick mustache who spoke no English didn’t

seem particularly concerned about giving us information or taking us

wherever we wanted to go. With Sergei number one translating, he gave

us the basics of the site, what was going on now, who the people inside

were what they were doing, etc. Basically it was an FAQ for the tour,

designed to cover most of the inane stuff ahead of time.

(Sergei, of the Ministry, Sergei of the tour company, and Vasily)

I should mention here that they didn’t give us a great deal of

information about the accident itself. If we asked, they would answer

questions, but the tour was basically about what was going on now, and

seeing some interesting sights. I’d gone to the Chernobyl Museum in

Kiev two days before, and I’m glad I did, as it gave me a good overview

of what had happened before seeing the aftermath. I can’t say enough

good things about the museum. My only complaint with it was that none

of the text was in English and there were no printed guides available

in English either. I got incredibly lucky and ended up catching an

English Language tour that was starting after I’d been most of the way

through, so I went back and saw most things a second time, but now with

explanations. Like most historical museums, this one had a full

sampling of media and photographs and told the story of what happened,

but in addition to that, it also had more real artwork than any

historical museum I’ve ever visited, which gave it an extra bit of

insight.

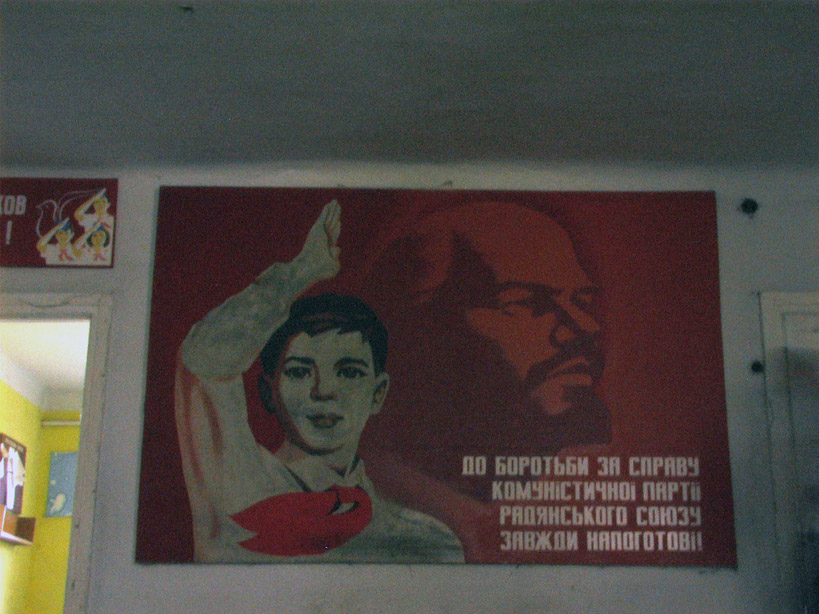

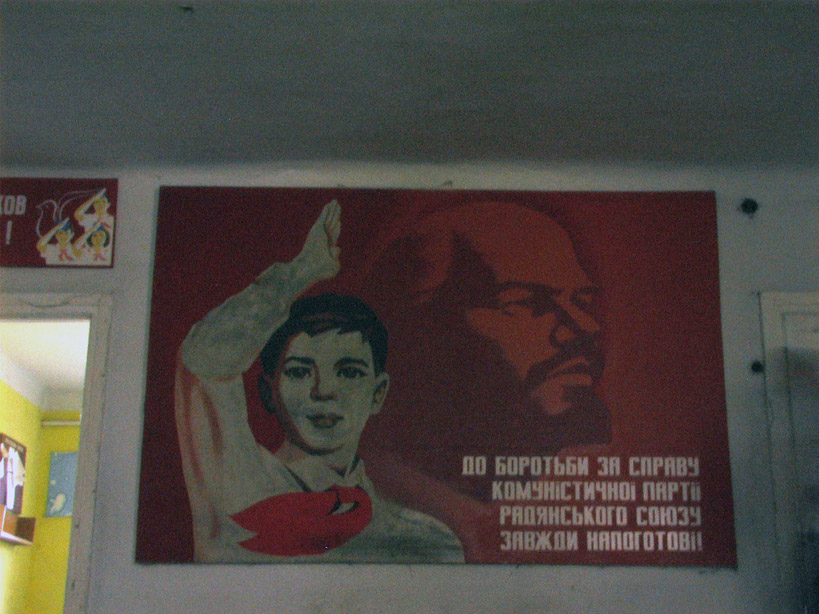

On display at the time I was there was a huge selection of posters that

had been made for the 20th anniversary from all over the world. Maybe

the most affecting thing was very simple. In Ukraine, and most of this

part of the world, the signs marking the city limits are simple white

signs with a black border with the name of the city you are entering.

On the back, and the sign you see when you are leaving, is the same

sign, but with a red diagonal line through it, telling you that you are

leaving that town. At first I thought it was odd, and it made me think

things more like “No Riga” rather than “You are leaving Riga” but after

a while I got used to it. Well, when you walk into the museum, and up

the steps, dozens of these signs are hanging from the ceiling above

you, the ceiling is full of them, showing the names of all the villages

and towns that no longer exist. It’s a good display that shows you the

full impact of the accident – just how many cities are no longer

inhabited. But then of course (not “of course” as it was a surprise to

me, though it shouldn’t have been) as you walk down the steps, leaving,

you see the backs of the signs - all the same city names, but with the

red slash through them – and suddenly that red slash takes on the other

meaning. You’re not leaving Privyat. Privyat doesn’t exist any more. If

you want to know what I love about art and what fascinates me – that is

it in a nutshell.

I’ve written these last few paragraphs in the early morning of 11

September. Maybe its weird that I’m spending so much time talking about

another country’s disaster on this date, but distanced from the US,

I’ve heard almost nothing about the 5th anniversary of the attacks,

just some things on BBC news a couple nights ago as I was getting ready

for bed, about preparations for the ceremonies. I’m sure you’re all

being inundated with it though, and anything I would say would just be

repetition of someone else. In any case, looking at my watch, the date

did jump out at me, and I had just a few minutes to consider it before

my writing time is up. Now I’m off to get breakfast and then meet my

fellow kayakers as we begin our first day.

Later on that night:

It’s around 10:30 and I’m sitting outside the hotel after the rest of

the crowd has gone to bed. Today was a really good day. The rafting was

mediocre, at best. The river is very small, smaller than pretty much

any river I’ve been on, in fact, but the water is amazingly clear and

extremely cold. My fellow tourists though, are fantastic. We had a

great time today, and then had dinner and went out to the bar across

the street for a couple drinks, and we’re already good friends. I was a

little afraid that I’d be the one loner among a couple large groups of

friends, but as it turns out, about half of us, or maybe even more, are

all here by ourselves. It’s going to be a good week, even if the

kayaking isn’t quite up to the level I was hoping.

Being the only one who was still reasonably awake, as Liam, my

roommate, was going to bed, I took my laptop outside and am sitting

under the stars, listening to a lone cricket off to my right, and other

than that, few sounds at all. There’s the hum of the hotel heaters and

AC and an occasional car on the road in front, and that’s about it.

This moment, basking in the fun of the evening, enjoying the stars and

the night, is what this trip was all about.

I’ll get to a bit more about Bovec and my new friends in a while, but

for now, I want to push through and finish my thoughts about Chernobyl.

After we finished the standard introduction to the tour, all of us –

two guides, a driver, three Scotsman, and me – got on the blue tank

like bus and drove further into the exclusion zone. At 10km from the

reactor, there is another roadblock and checkpoint, and then moving

past that, you’re into the heart of it. Our first stop was the

beginnings of a museum/graveyard for some of the equipment that got

used in the cleanup.

Reading from the web, it seems there is a real graveyard for these

vehicles, but the tours are no longer allowed to go there, whether its

due to radiation or bureaucratic reasons, I don’t know. This place only

had about six or seven vehicles, and so we didn’t stay long… just long

enough to take a few pictures and set the geiger counter down on the

treads of the tank and watch it register a much higher reading than

anywhere we’d been previously.

After that, we drove to the power plant itself. The first thing we saw

was the construction site of reactors 5 and 6 which were nearly

completed when #4 exploded. The buildings are exactly as there were

twenty years ago, with the cranes and construction equipment still

surrounding them.

From there we drove around, and stopped at the main station, where

plants one and two still stand (they were functional until 1996 or

2000, depending on where you get your information) and there is a

bridge where the workers spend their breaks feeding the catfish from

the river. Since no one fishes here, and nothing else disturbs them, a

few of these have grown to massive proportions – a good six feet in

length. Growing up on the Ohio river, I always used to hear stories

about the catfish as big as people, but of course I never saw them.

Well, for those of you who don’t believe… here are pictures. For

reference sake, the small ones you see next to them aren’t small at

all. Each one of them is bigger than any fish I ever caught, and some

maybe as much as 18 to 24 inches long. As you can see, the others dwarf

them. Despite what you might think, that size isn’t due to radiation or

anything though… its simply a function of living for 20 years in a

place where man isn’t fishing or hunting. Much like the rest of the

exclusion zone, in fact.

From the bridge by the main station, we simply drove around the

building and were suddenly looking up at the reactor #4 building.

The picture shown is as close as we were allowed to get, and in fact,

we were told specifically not to take pictures of anything in that area

besides that building. I couldn’t get a straight answer why… from what

they said the other buildings were simply holding contaminated

materials and waste, but they were quite insistent. There were a few

workers there who looked at us a bit, and for the first time that day I

felt a bit weird about being a tourist where this tragedy had happened,

but at the same time the intrigue of the situation overcame it, and I

snapped a few photos.

Again we didn’t linger. After getting a few photographs, we got back on

the bus and headed away from the plant, across a bridge. Halfway

across, we stopped and were allowed to get out and shoot more photos.

Around this time I started getting the impression that this tour was

basically about taking your pictures and showing your friends that you

were there, which made me feel a bit weird again. That feeling never

really went away after that, and was reinforced several times, though

Vasily, the driver did his part to get rid of it.

After more photos, we continued along the bridge to the center of the

city of Privyat. As I said above, it was a Soviet model city, and so

the main square has a Culture building in the center, which was the

center of the Soviet Government, and on its left the hotel, and on the

right the restaurant. Spread out around those are many buildings where

the citizens lived. Parking there, Sergei told us we could take 20

minutes or so to wonder around. The Scottish lads went straight into

the Culture building, and never really left there. I knocked around the

whole square a bit, scaring a black snake (that scared me as well),

finding a doll that almost seemed like it had been planted there for

photo opportunities, and exploring the area as much as I could in the

time allotted.

It was from this point that my impressions of the deserted areas began

to get confused. From here throughout the rest of the areas we saw,

there seemed to be an enormous about of destruction. For instance, in

all these buildings, the glass was long gone and the buildings were

literally wrecked. It was almost as if the force of the explosion had

reached here, but of course it didn’t. Even now I find myself wondering

how so much stuff was destroyed beyond recognition. Did vandals really

sneak into the zone just to tear shit up? Do things really deteriorate

this quickly with no one there to do maintenance? Did the weather blow

out the windows? I have no idea, but several other places we went

felt the same way. I looked at them and felt as though I was seeing the

ruins of an explosion rather than simply places that had been abandoned

for twenty years. No answers seem to be available, though.

Some of it seems to have to have been vandalism though, as I found

these painted images on the side of one of the buildings. It’s kind of

amazing to me that someone would go to the trouble of sneaking in to

paint on the walls of Privyat, but there’s no denying its truth. The

spray paint is there to be seen.

After meeting back at the tank, we drove up a road that was even more

overgrown than most of the others. I haven’t mentioned it, but every

road we were on was being overtaken on either side by vegetation.

The pavement was still very good for the most part, but veering too

near either side meant being slapped and scratched by branches that

hadn’t been trimmed in two decades. We drove up this smaller road

though, and parked seemingly in the middle of nowhere, and

without a word, the two Sergeis got out and started walking through the

brush. We walked through the trees, then into a building (maybe a

school) and back out, along a walkway that had something I can only

guess was the remainders of electrical signs along them, as well as

some sort of rectangular kiosks with classical Soviet artwork, and then

stepped out into a clearing that was obviously the center part of what

was once an amusement park.

Sergei and Sergei never even slowed down. They just kept hiking,

leaving us to stop as we wanted, taking photographs, but then having to

run to catch up. I stopped under some willow trees to take one last

shot of the rusting Ferris wheel, then ran up the road to where the

truck had turned around and driven to meet us.

I was the last one in, beginning to feel even more badly about this

tour of these deserted cities where we just took pictures and ran along

the paths, not learning anything more about the people that lived

there.

From there, we drove up the road until Vasily turned off on a sandy

patch and swerved around a barrier with a sign that probably said “No

Entry”. He drove up the road until the wheels began slipping in the

sand and one of the Sergeis leaned forward and told him to stop. Once

again we all piled out and started walking into the field, and soon

into the trees.

There were a couple false starts as Vasily, leading the way, tried to

find what was left of the road. Eventually with the three of them

talking and comparing notes, they found it, and we hiked for about a

kilometer through the trees and the underbrush, seeing an occasional

abandoned house or building. After a while, we came into the remains of

a playground, and saw through the trees what was left of a schoolhouse.

One by one we filed in, and saw the remains of where Vasily went to

school forty years before. Once again, I found myself feeling like this

was the scene of an explosion or disaster rather than just an abandoned

building. Desks were piled atop one another, posters and classroom

materials were thrown on the floor, and windows were broken. I couldn’t

help wondering who took the time to do this much damage to the school

before leaving town. Even more so this time, I walked through the

building taking pictures, but feeling like I was intruding on all the

people who had lives there. Vasily seemed fine with it though, and

walked around himself, looking into each room and telling us, in

Russian, “This was Historia, This room was Sciences.” And so on. All

the time, I was looking around, trying to note details, and wondering

what it would feel like if it was my school I was walking through.

As we were looking around, I found three photos on the floor of

students who had gone there – obviously school pictures, of three

girls, in their early teens, each wearing school uniforms. Something

about them struck me, and so I picked them up and carried them over by

the window, and took a photo, and then headed for the main lobby, where

the group was congregating again.

Sergei was carrying some posters that he picked up from one of the

classrooms, and seeing that, I realized that I couldn’t leave the

photos behind. So, I went back to the room, grabbed the three pictures

off the desk and stuffed them in the side pocket of my pants. Don’t ask

me why I couldn’t stand to let them stay there, but I couldn’t. Even

though I didn’t know there names, and knew Vasily didn’t either, I felt

like it was important to take them out of the destruction, so that they

would be seen by someone. I had (have) no idea how much radiation the

silver in a photograph will hold, but it seemed like the right thing to

do.

So then we all met again and left the building. Once again Vasily led

the way, and this time we walked just through a small field and into

another building. This one was the kindergarten associated with the

other school, and in the very first room there was a pile of about ten

or twelve stuffed animals and dolls in various states of decomposition.

I took one photo of them, and couldn’t’ stand it. I turned the camera

off and just walked around, seeing toys and playthings of young

children in every room. Finally I couldn’t take any more, and stood by

the front door, waiting on the others to finish, and as I did, Vasily

walked out the front door and into the yard, shook his head sadly, and

said simply, “Da.” It only means “yes” of course, but it was one of

those moments where language seemed so much more basic and simple than

any other time, capable of expressing an entire range of emotions with

one word.

We hiked out of the woods, and back to the bus, with the rest of us

waking all the way back to the road and Vasily driving it out of the

sand backwards, spinning the wheels, charging through the soft dry

sand, and convincing me that he really was a badass when it came to

driving. We got back into the van and once again our three guides drove

us to another photo opportunity. This one was an old shipyard, on the

river, with the hulks of rusting boats half beached, deteriorating.

I took some more pictures around there, and then soon enough we drove

back to the Ministry of Information headquarters, stopping at the 10km

checkpoint to let them sweep the bus with a geiger counter to make sure

we didn’t pick up any radiation. At the ministry, we each stepped onto

a small machine that looked a lot like the scales at the doctors

office, put our hands on the plates and waited for a green light to

show us that we were clean. After a short wait, we were served lunch.

At first it was a pretty light plate, and all four of us thought it was

a good, but not particularly filling lunch. But then came vodka shots

for everyone, complete with a toast (always there is a toast, and

always an odd number. They take their drinking very seriously here.)

and then another course, and by the time the five courses were done,

along with several more vodka shots, we were all stuffed and also

happily buzzed (all except Vasily, who was driving and didn’t have

any).

After lunch we started back and had to stop again at the 30 km

checkpoint, this time having to get out and walk into the building.

Sergei showed how to step into the large metal grates that checked us

for radiation yet again, and I had a tense moment where I remembered

the three photos in my pocket, wondering if they were going to set off

the alarms, and if they did, how I was going to explain myself. No

green light this time, but no alarms either, and Sergei gave me the go

ahead to step through, so just like that we were back on the bus and

officially outside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

We drove back, talking a bit, and stopping by the side of the road for

Sergei to buy some mushrooms (setting the geiger counter on them first,

of course) and then dropped him at his car a few miles later. From

there it was just the four of us and Vasily going back into town, with

him weaving in and out of the traffic like a formula one driver and us

holding on for dear life. He dropped us off at the hotel where we met

that morning, and as I was getting off the bus, I used what little

Russian I know to try to thank him for taking to his school He seemed

to understand, and we exchanged a good friendly handshake – yet another

small thing that I’ve learned can express a great deal on this trip,

and then he pulled off back into the traffic to take the blue tank

home.

It’s now September 15th, and just like Auschwitz, it’s taken a great

deal of time to write about this trip (actually just one week, but it

seems like much longer). I’m still not entirely sure what to think

about it. I’m glad I went, and if I had it to do over, I’d definitely

do it, but at the same time it leaves an incredibly sad feeling. The

strangest thing is still just how much damage has been done to almost

all the buildings we went in. I have to keep reminding myself that the

human casualties were not on par with the amount of destruction I saw.

The children from those schools aren’t dead, nor are the people from

that town, or at least most of them aren’t. A few no doubt have had

their lives shortened by the radiation, but for the most part, the

higher incidences of cancer and similar diseases that have been

expected haven’t really shown up yet. Obviously there have been some,

and a certain number of people have died from the accident, but it’s

very tricky figuring out how many other than the firefighters, miners

and military people who helped clean the whole thing up in the first

six months. Touring the sites, and thinking back on it, I have to

remember that a lot of those people, like Vasily, are leading normal

lives. The one difference is that they can’t go back home, to where

they grew up, and where their parents lived or any of those places. For

me, and I think for most of my friends that would be a big loss. For

the Ukrainians, especially the older ones who are tied much closer to

the land than most Americans (excepting the farmers and few who still

really work on the land), it’s a much bigger loss. But they are strong

people, and move on, living in Kiev, or wherever they have been

resettled, and occasionally kicking the dirt and saying “Da” when the

sadness and regret are felt the most.

As I said, it’s a week later, and the past week has been amazingly fun,

with great weather, amazingly great people, and lots and lots of

activity ( as well as bruises). As I type this though, it’s pouring

rain, and we had the morning free, with the possibility of a rafting

trip this afternoon. I’m looking forward to telling everyone about this

week, and the great people I’ve met, but it’s important to get this bit

up first, and show some of the things I’ve seen. I’ll write again soon,

but for now I am going to spend some time with those friends and enjoy

the free day, the rain, and compare our bruises.

Love to you all,

Stephen